When designers look at a sofa, they notice the color of the fabric, the shape of the arms and the materials used to hold it all together. When clients look at a couch, they might consider the color and style, but almost always, their focus will narrow down to one point: How hard is it going to be for me to clean this fabric?

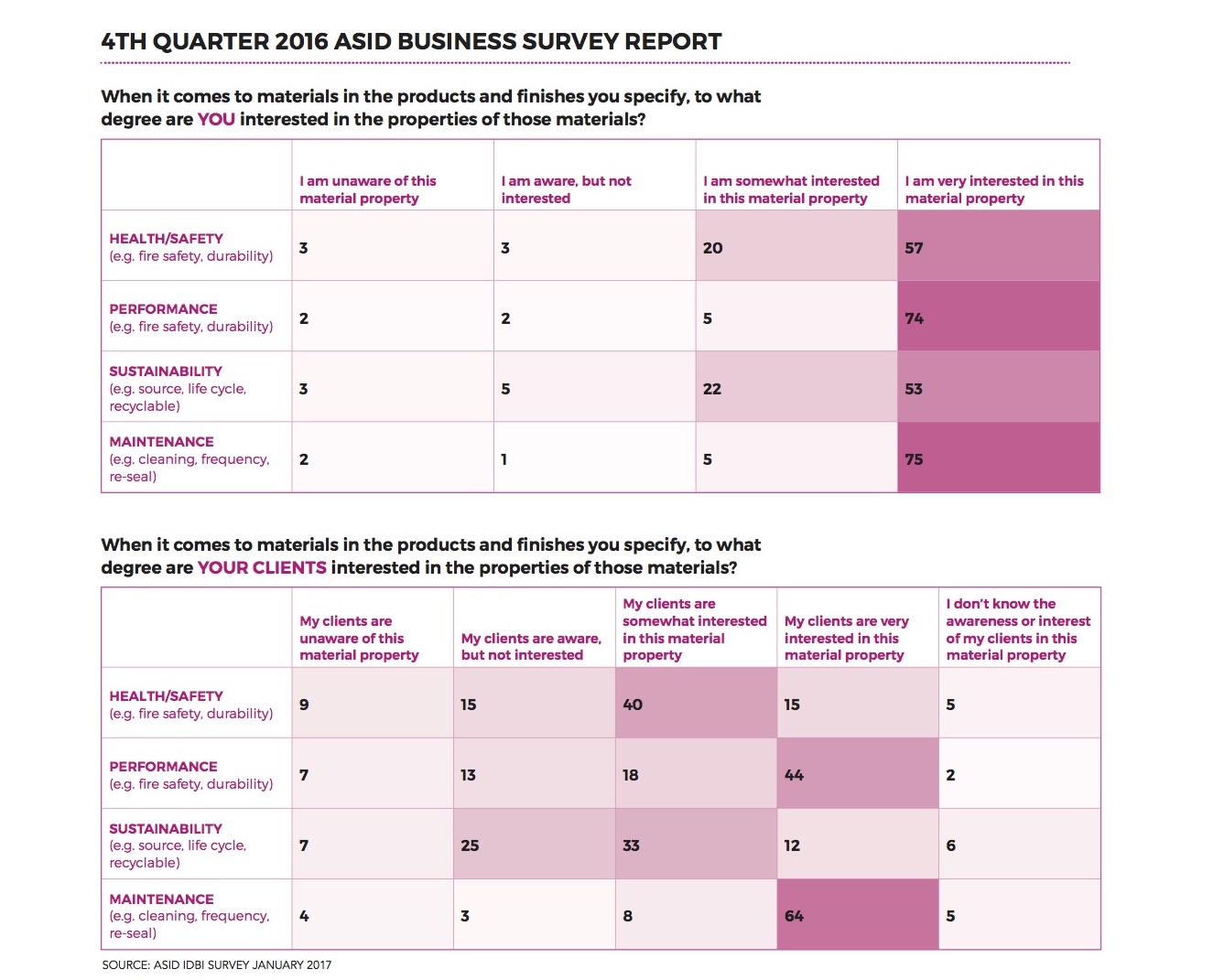

Performance and maintenance matter most to clients, according to research from the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID). Last January, ASID asked interior design firms in its 2016 fourth quarter business survey: When it comes to materials in the products and finishes you specify, to what degree are your clients interested in the properties of those materials?

Not surprisingly, more than 76 percent of respondents said their clients were very interested in the maintenance (cleaning, frequency, re-seal) of products, and 52 percent said clients were very interested in the material’s performance (fire safety, durability). Few firms said their clients were interested in the health/safety (14 percent) or the sustainability (14 percent) of product materials.

On the other side, designers felt differently. When asked to what degree were they interested in the properties of those materials, almost 80 percent said they were very interested in the health of the material, and more than half said they were very interested in the sustainability of the material.

Designers know that the health and sustainability of materials matter just as much as the performance and maintenance, especially when it comes to toxic flame-retardants in upholstery. So when clients don’t want to help themselves, it’s up to designers to take charge.

How to Make Clients Care

Both Robin Wilson and Kari Whitman have built interior design firms that represent healthy and sustainable design respectively, so most of their clients come to them specifically because they share those same values. For the outliers, Wilson and Whitman have their strategies.

Wilson says she gives her clients the choice between two similar products — one clean or sustainable and one not — and lets them choose. When she finishes the installation, Wilson tells the consumer if they chose clean or sustainable products.

But what if the client chooses a less-than-quality product? In most cases, Wilson can persuade her clients to choose the clean product by guiding them through a series of questions. If the choice were between an incandescent and LED bulb, Wilson would first discuss the cost. Is it the same? Nowadays, LED bulbs are comparable in cost to incandescent. If that’s not enough, Wilson explains the differences in longevity between the two. LED bulbs can last for 25,000 hours compared with 10,000 for incandescent bulbs. Finally, Wilson will point out safety features: LED bulbs run cooler, which means they’re less likely to start a fire. In the end, clients almost always choose the clean and sustainable products.

“You’ve guided them without telling them what to do,” she explains.

Of course, designers can lead a client to the store, but they can’t make them buy. If clients still choose the less sustainable option, Wilson backs off.

“It’s not your home, it’s the client’s,” she says. “You give them advice, you educate them and they ultimately make the choice.”

While the persuasion tactic works well for Wilson, Whitman employs a more direct approach.

“I don’t show products that I don’t feel are sustainable,” she says.

Whitman, a self-described tree-hugger, works exclusively with high-spending clients, and few of them care about whether or not a product is sustainable or eco-friendly. They’re mostly interested in its aesthetic, she says. Her clients want pieces that are timeless, something they won’t grow tired of in another year or so.

Usually, clients don’t ask Whitman what product materials she’s using, but on the off chance a client explicitly states that he or she does not want the more sustainable product because it is more expensive, Whitman will first try to find a more cost-effective yet sustainable option. If that doesn’t work and the client remains unmoved, Whitman will offer to pay the difference on the more expensive sustainable choice.

“If I can’t find something that is the same price or less, then I try to make a large statement.”

In most cases, the guilt trip is enough to convince the customer. It may sound like a rough tactic, but Whitman never hides her environmental commitment and will do everything possible to promote sustainability.

Designers as Educators

Clients hire interior designers specifically for their expertise. So if designers are truly interested in healthy and sustainable products, then it’s up to them to be educators and teach their clients, even if they seem uninterested.

“I think we care more,” Wilson says, “and I think we as designers are driving the conversation to the consumer, who is gaining awareness.”

But even for designers, there’s a lot of disinformation out there, and becoming a resource for clients means that designers themselves need to read up on healthy and sustainable product materials, which means going beyond marketing.

The Sustainable Furnishings Council (SFC) and ASID serve as great starting points. The SFC website offers plenty of information on companies and product materials, and access is free. It’s also worth checking ConsumerReports.com for more information on specific products.

Wilson recommends going to at least one major market in High Point, Atlanta, Dallas or Las Vegas to meet with manufacturing representatives. This gives designers immediate access to the companies whose products they use all the time, so if designers ever have a question about a material the company uses, they know who to call.

Connecting with representatives doesn’t absolve the designer from doing outward research. As Wilson and Whitman know very well, the rules governing marketing language for organic, sustainable and clean terms are not absolute.

“There are no federal guidelines in durable goods that specify what organic, natural or sustainable is,” Wilson explains, “and in some cases, companies use those terms liberally without any certifications or research because it’s great marketing.”

When Whitman has a question about a company or material, she heads straight to Global Green, a non-profit organization that raises awareness and educates people about sustainability and climate change. The organization also helps communities become more resilient and rebuild green after a natural or human-made disaster, and it helps implement environmental policy. Designers can find plenty of green tips and resources at GlobalGreen.org.

Global Green is especially concerned with companies that “green wash” — advertising themselves as “green” without implementing any actually sustainable practices. Global Green works to call out companies that intentionally use vague marketing terms to appear green or sustainable without doing the work.

Deceitful marketing aside, clients won’t begin to care about the health and sustainability of materials until more designers make them. By being an educator, designers are uniquely positioned to change their clients and the industry.