In 2016, Kerri Hall drove an hour from North Carolina to Virginia to pick up items she’d bought at an auction. Vaughan Furniture filed for bankruptcy and had auctioned off equipment in its factories. As she stood at the finishing line looking at all the hangers that moved the furniture along the conveyor belt, she suddenly felt the weight of globalization and her role in it fall on her shoulders. Though her life and business had also been uprooted by globalization, this was the first time Hall — a 25-year veteran of the furniture industry — witnessed firsthand what her design and sourcing business had done to the industry and to the hardworking people in the factories.

We know the globalization story: Countries became more connected through the World Trade Organization and trade agreements, and lured by the promise of cheaper labor and materials, furniture manufacturers started importing from China, Taiwan and other countries. Then they started closing U.S. factories, moving production overseas almost entirely and leaving towns in Virginia, North Carolina and other states in the dust. But the story’s not over. Not by a long shot.

While other companies moved overseas, furniture manufacturing evolved in the U.S., launching a new generation of furniture manufacturers committed to high-quality, innovative and job-creating products. They may not have factories with hundreds of workers and smoke stacks that brush the sky, but their ever-adapting spirits embody what it means to be “Made in America.”

The Hunt for High Quality

Inspired by her visit to Vaughan, Hall thought of ways she could use her talents and connections to bring furniture manufacturing back to her area of the country, and right away, she spotted a need the market wasn’t currently meeting: heirloom-quality upholstered furniture sold online directly to the consumer and shipped at a fraction of the traditional cost.

As the idea started to form in her mind, Hall contacted a high-end upholsterer she knew in North Carolina who was struggling to compete with other domestic and international high-end manufacturers.

“When I came to her and showed her the idea and brought her my prototype,” Hall says, “I said there’s gotta be a better way to do this than for you to make the product, for you to sell it to somebody — to a retailer, a wholesaler or a designer. They then sell it to their consumer and put two or three markups on it. Why can’t we have this product that we sell on the internet because everyone’s buying everything on the internet?”

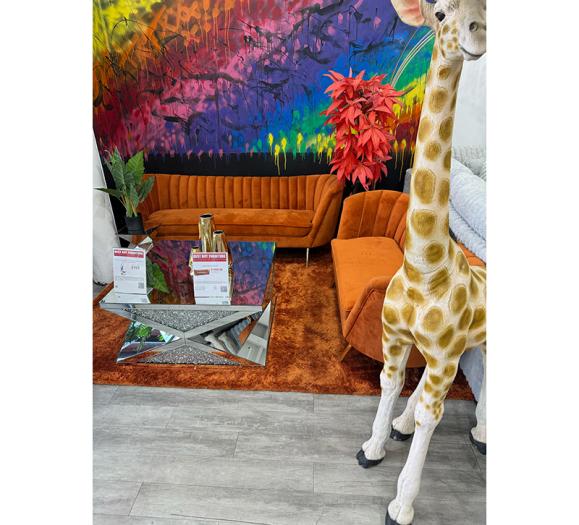

Hall’s concept centered on simplicity. Through the website, consumers would choose from several designs, about 20 fabrics, another 10 accent fabrics and different leg sizes and finishes to create their own sofa or chair that would then be produced in a matter of days and shipped in three flat-ship boxes to the consumer’s home where it can then be easily assembled and disassembled. The result became MicMag By Me.

“I‘ve had at least 15 to 20 people say to me ‘If I never move another heavy sofa again, that will be the best day of my life,’” Hall recalls. “It not only goes together but it also disassembles very easily and you can put it together again easily. Anytime you put it together or take it apart, it doesn’t disrupt the integrity of the mechanism that we have, and it makes it easier for them to live with their furniture for a very long time.”

New Consumer Expectations

In the back of her mind, Hall was looking for a way to capitalize on Swedish giant IKEA’s strategy of build-it-yourself furniture without sacrificing the quality. On the other side of the country in Emeryville, CA, Campaign Living had been trying to solve the same conundrum for the past three years. Their solution? Laser-cut, powder-coated, cold-rolled steel frames that can be easily put together and produced separately from the upholstered section.

“When you’re buying upholstery,” Brad Sewell, CEO and founder of Campaign Living, says, “usually the first thing that wears on the product is the fabric, and once that fabric stains or wears or gets torn, you’re kind of stuck with a frame that you might want to keep. But reupholstering is really the only option to breathe life back into the product and replacing the fabric and potentially changing the foam. And so we really wanted to disconnect those two things in our product and separate ourselves from anybody else in our market. We couldn’t understand why you could change the tires on your car, but you couldn’t change the fabric on your sofa.”

Sewell may not have started his career in the furniture industry, but his engineering experience with auto manufacturing and a brief stint as an engineer at Apple gave him insights into what modern manufacturing looked like, and the name of the game is fast service at a fraction of the expense. It takes just four to seven days for a sofa to reach that doorstep, depending on the customer’s location.

Like MicMag, Campaign lets customers build their own product. Its sofa comes in seven different fabric options and two finishes for the wood legs, and each one costs $1,195. The loveseat costs $895 and the chair $595. Customers can also purchase additional pillows and slip covers so the sofa becomes a living piece of furniture, able to change as the needs and tastes of the customer change.

Down in Los Angeles, Nathan Anthony Furniture, which opened its doors in 2005, might not be able to ship product in a matter of days, but the company shares the same spirit of customization. Nearly every product can be customized, and considering Nathan Anthony’s high-end customers, flexibility is a vital component of the business.

“You really can only do flexibility when you’re passionately involved in every aspect of the business,” Co-founder and Principal Designer Tina Nicole says. “Almost every time we make something, it’s different.”

Lean Innovation

Nicole’s known for having a keen eye for furniture and market trends, and in 2007 when the recession hit, she steered into the skid. She knew the demand for custom, high-quality furniture still existed, so while her competitors sent their manufacturing offshore, Nicole and her husband and co-founder Khai Mai stayed local.

“When you’re flexible in custom,” Nicole explains, “you don’t want to move offshore because you lose control. You lose your ability to keep your promises on when you’re going to ship. The integrity of the components are very important to us too when you have a quality product.”

Mai, who first worked in a furniture store with his father at age 18 and co-owned a mattress factory by 23, and Nicole practice a form of lean manufacturing that produces little waste and high-quality products. Production starts with a sketch of the product, which is then uploaded to a computer-abled design (CAD) machine. Once the pattern is finalized, a computer numerical control machine will cut the fabric and wood as needed.

Nicole and Mai source all the components for their products from U.S. companies, but they don’t order them until a customer orders a product, which helps reduce waste and save money. No one ever lifts heavy furniture. Mai added wheels to most carts all over the factory, so no one has to risk a back break to do their job. When working on an order, each person on the production line receives a kit with everything needed to complete that portion of production. Nicole says this method has helped Nathan Anthony triple its production within the same space.

“The waste company used to come to our factory every day,” she says, “and now they come once a week, so that’s a big reduction in waste.”

Campaign started production after the hardest years of the recession, but having watched manufacturing change, Sewell knew a lean method would be vital. At Campaign, production starts when a customer places an order online.

The parts of the frame are then cut using lasers and welded by robots to ensure precision and accuracy. Machines also cut the wood legs so each leg comes out identical. The covers on the cushions are all hand-sewn, and once the product is finished, it’s packed in boxes and shipped. Sewell says the company relies heavily on CAD to 3D imaging to create products and send designs from California to factories in Alabama and Mississippi.

“The furniture industry doesn’t always adopt modern manufacturing technologies, probably because they haven’t had to or the people at these companies don’t have experience doing it,” Sewell says. “In the automotive and electronics industries, they don’t have a choice. They’ll be out of business if they don’t adapt.”

Jobs for the Future

For much of her career, Hall worked one step ahead of globalization. Her dad had been importing products from Taiwan for Sears long before anyone else thought of going overseas. For almost 20 years, she worked as the go-between for U.S. furniture companies and Chinese manufacturers. She would design the product, sell it to furniture companies, orchestrate the production and fulfill orders.

But in 2014, her clients cut her out of the picture and went to the factories themselves. It was the year she planned to pay off the rest of her home, the year she’d been working for 20 years to reach, and it was all gone. Standing in that factory two years later, she felt profound remorse for those factory workers losing their jobs, and she promised herself she would find a way to rehire some of them.

Hall currently employs about 25 people in the factory. It may not seem like a lot, but Campaign and Nathan Anthony, for comparison, employ between 40 to 60 people in their factories.

“Most of the people in these factories have trade skills and have been working in factories for many years,” Sewell says.

All three companies hope to expand and hire more people, but globalization isn’t the only disruptor. Automation is changing the jobs, potentially creating more, says Sewell, if done effectively. Right now though, the U.S. labor market is struggling to fill positions for skilled workers — those who know the trade and the latest technology. No factory will be devoid of humans, but better technology means fewer jobs for low-skill workers.

This new crop of American manufacturers has mastered lean manufacturing, and they’re dedicated to growing their companies without wearing out their employees. Nicole and Mai’s efforts to make labor jobs more comfortable and easier helps reduce turnover, and at Campaign, Sewell plans to expand production to tables and bed frames.

As for Hall, she recently filed MicMag By Me as a B corporation with plans to help fund a local multi-generational single women’s living complex and later fund shelters all over the country.

“I’m not in it just to make money,” Hall says. “I’m in it to put these guys, women, these single moms, these kids that don’t have the opportunity to go to college and are perfectly fine working in a factory for life, to give them good, meaningful jobs.”

Manufacturing is returning to the U.S. Here’s why.

Harry Moser, founder of the Reshoring Initiative, says manufacturing is streaming back into the U.S. Between 2010 and 2017, 86 furniture companies reshored and restored 8,629 jobs. These factors made a difference.

Short-term

The 2016 election: It’s not uncommon for businesses to get excited when a Republican gets elected (the same happened in 2000) because it often leads to tax cuts and deregulation. Moser says in 2017, there were 169,000 job announcements from companies reshoring in the U.S. Those jobs won’t be filled for six months to a few years, but for now, that’s an optimistic outlook.

Tariff potential: Companies may want to reshore to avoid paying a tariff.

Competitive dollar: Strong, but not too strong. When the dollar is slightly weaker than other currencies, it’s less expensive to produce in the U.S.

Long-term

Chinese wages: According to Moser, they’ve grown by 10-15 percent per year for the last 15 years. Previously, Chinese wages measured about 5 percent of what American wages were. Now, they equal as much as 25 percent of American wages.

Productivity: Chinese workers produce about one third to a half as much as American workers in the same timespan.

Made in the USA.: Customers like supporting companies that produce in the U.S.

How to bring more back

Moderate policies: Moderate and business-friendly policies work regardless of political party.

Skilled workforce: U.S. skilled labor can’t compare with Switzerland and Germany, Moser says. Investment in trade and vocational schools could go a long way.