Despite the near weekly headlines about store closings across the country, Andy Bernstein, Founder of FurnitureDealer.net, is convinced that “we’ve passed the mid-point of the so-called retail apocalypse. While there are still more store closings to come and it’s hitting our industry really hard, I believe we’re actually on the front end of a retail renaissance.”

To achieve that renaissance, however, Bernstein says that conversations about profitability — long focused on price and reducing costs — need to substantively change. “We need to start talking about today’s consumer because we’re witnessing a fundamental shift. It’s very difficult to understand this from a generational standpoint because Boomers equate everything they buy with value for a price, but today’s consumer is really different because they are less about value than they are for convenience. The problem is that even while most of us are becoming today’s consumers in our personal lives, we are still thinking like yesterday’s consumer on the job.”

He uses as example bike share and scooter rental businesses that have become routine in many U.S. cities. “To a Boomer, it doesn’t make sense to rent a bike when you can buy one for a couple hundred bucks,” Bernstein says. “Why would you rent by the minute, when you could own the darn thing? Well, for today’s consumer, buying a bike is inconvenient. You have to have somewhere to store it, and it’s never right where you want it when you need it, and you have to lock it up when you get to where you’re going. For today’s consumer, renting a one-way bike is super convenient, and by the way, less expensive than a one-way Uber.

“A well-known industry executive countered that convenience has always been a strategy, and he pointed to drive-throughs to make his point,” Bernstein recalls. “But a drive-through is not really convenient. You have to go to the restaurant, wait in line, explain your order to somebody, take out your credit card, drive to the next window and wait for them to hand you your order. Today’s consumer doesn’t want to do that. They want to sit right where they are, pull out their smartphone, look at every single possible option available, press a button and have some dude deliver their order, wherever they are, with or without a tip, which by the way is a choice the consumer can make anonymously.”

Inconvenient Truths

According to Bernstein, the home furnishings industry is currently witnessing a number of internet business models, such as furniture rental, that seem to make little sense when viewed strictly from the standpoint of value. “For today’s consumer, it’s really inconvenient to have furniture delivered, and it’s even more inconvenient for people to have to deal with furniture when they want to move. The rent-to-own model aimed at yesterday’s consumer was about lending money to people who couldn’t afford to get credit. The new model offers stylish goods and the convenience of pick up and/or switch out if you decide to move.”

He points to Target’s new app as another example of convenience consumers are being taught to expect from businesses of all kinds. “If you had asked me about Target a year and a half ago, I would have said they were going to close stores, and potentially go out of business, because Amazon was so much more convenient. But now, Target has upped Amazon with a shopping app that literally calculates available coupons and discounts [and] gift card earnings, and makes store pick-up incredibly convenient. You can choose same-day delivery through Shipt, or you can choose which store you want to visit to pick up your goods. They send an email when your order is ready, and you click a button to let them know when you’re on your way. GPS tracks your progress, and as you pull into their parking lot, you get a message on your phone that says, ‘It looks like you’ve arrived.’ You drive up to the front of the lot, and some kid comes out of the store with your purchase, loads it into your car, and you sign with your finger.

“As an industry,” he exhorts, “we’ve got to get our butts in gear, and make the investments necessary to make us just as convenient to deal with, so that home furnishings stores can offer similar kinds of awesome experiences. Companies must step up now. We have to get out of this mentality that profitability means cutting corners, because now it’s all about what your customers are saying about you, and in order to make raving fans, you need to delight the hell out of every one of them. We have to think long-term today, because we’re in the middle of a disruption. If you’re just focusing on short-term profit, I predict you’re going to die.”

Let Me Be the Judge of That

The challenge, retailer Chris Pfeiffer believes, is that independent brick-and-mortar stores are held to higher standards than their mass and online brethren. “A consumer will go online and click on a $3,000 Chesterfield-style sofa and then they’ll come into our store looking for a chair to go with it, and they will agonize for two or three days about the comfort of that chair,” he relates. “They’ll purchase a sofa they have never even sat on with one click. But in store, it’s a process, and they are very particular about the fabric, the color and the comfort. While you might think we’re dealing with two different customers, we’re not. The same customer will buy products online without thinking about anything other than whether it will look good, and they will accept a top-price item with D-quality construction and comfort when it arrives. Yet, their scrutiny of product in store is much higher at the same price point.”

Pfeiffer is Managing Partner of Homestead House in Conroe, TX, and an experienced merchant who has spent decades honing his retail chops, first as a corporate general manager for American Furniture Warehouse in Denver, CO, and later in management roles at Homestead House in Denver and Louis Shanks of Texas, where he learned the high-end of the business inside and out. Eight years ago, he opted to open his own high-end store. He is quite familiar with the concept of a retail apocalypse. “In Houston, we’ve probably lost 300,000 square feet of high-end retail,” he says. “I’m seeing stores folding all around us.”

While he attributes many of the closings to the pressures of internet competition, Pfeiffer thinks that success at the better end now is less about changing the way brick-and-mortar stores do business, as staying true to what high-end furniture retail has always been about. “We need to focus on what we do well, and that is interacting with consumers on a daily basis and educating them about quality. We’re asking them to invest more, and we need to make their shopping experience more personal and exciting, because that’s something you can’t get on the internet. We’re going to lose sales to Perigold and other online retailers because there are a certain number of consumers out there who do not like shopping face to face. You have to concede that business, because the internet is not going to go away, but that’s OK, because we would have lost those sales to something, somewhere.”

Indeed, he shares, “we’ve had people call in and say that even though we offered a better price than Perigold, they bought online anyway, and for them, it was because of the convenience factor.” On the other hand, he adds, “we get people in here literally every week who tell us they bought online, but it wasn’t the experience they thought it would be, and the so-called white-glove delivery was anything but. One customer told me he had guys in his house for eight hours trying to put a bed together. He finally went in and asked them what the problem was, and they admitted they’d never put a bed together before. He became jaded about white-glove delivery really quick. Another couple who bought an entire bedroom from us a couple of weeks ago said they realized that when the bed they originally ordered from Wayfair arrived, it wouldn’t last them more than a few months because it was so shabbily built. Online, low-end product looks better than it does in person.”

Even so, offline, the Houston marketplace is rife with low-end purveyors, “no middle,” and “too few high-end stores,” Pfeiffer says. Yet reports are that many of those that have trafficked in more promotional goods in the past are now looking to trade up. One reason may be that Pfeiffer’s former employer, American Furniture Warehouse, has moved into South Houston with a 300,000-square-foot store, and another store is nearing completion in West Houston. “Jake is the king of the low end. No one is going to compete with him there,” he says.

While others seek their level, 15,000-square-foot Homestead House is focusing on its niche and what it has always done best: communicating the benefits of buying quality furniture. “The Kardashians and some of the movie stars have begun blogging about fast fashion, telling their followers — Millennials — to quit buying crap that ends up in the landfills. They’re telling people to buy a nicer blouse, a nicer dress, skirt, boots, whatever, and to wear them longer. We’ve started telling them to buy better furniture and keep it longer. Unlike a $500 sofa, a $5,000 sofa will never see the landfill. We tell young people here all the time that the rich get richer because they don’t re-buy their furniture every five years. So, buy a few nice things, get them paid off, and then buy another nice thing.”

In merchandising Homestead House, Pfeiffer has flipped the typical good, better, best approach on its head. “We tell people that our store is laid out best, better and good. We’re very brand-centric with Henredon [Pfeiffer purchased the inventory when Heritage Home collapsed a few years back and is now arguably the world’s largest dealer], Century, Hancock and Moore, Sherrill, and Taylor King all up front. Better is Lexington, Stanley, Tommy Bahama, and good is Flexsteel and some solid wood lines. We spend a tremendous amount of time pulling out drawers, demonstrating the dovetailing, the hand-carving, the finish. We educate people about how the furniture is made, the difference between the brands and the quality.”

The Low Down on the High End

“A lot of brick-and-mortar stores are trading up in order to increase profitability,” says retail strategist and product and store designer Connie Post, remarking that selling low-end product offers few profitability advantages. “There is no bottom and there are no margins and that’s not sustainable. You simply can’t stay alive in the face of online competition.”

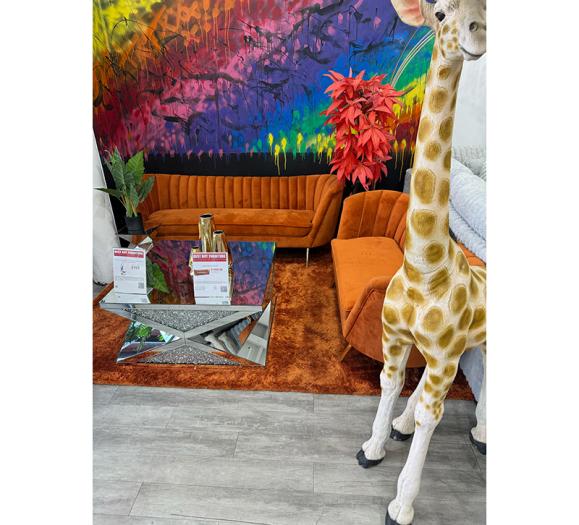

Post points out that “better product equals better margins,” and says the name of the game now “is to give consumers a reason to want to buy something better, to aspire to something of better quality. I think it’s essential now to group branded product into lifestyle stories. I’m not talking about the 7,000- or 8,000-square-foot galleries of old. Those days are gone, and I don’t care who it is: No manufacturer has that many good SKUs, and no retailer has that much real estate to give away. I’m talking about creating boutique environments — 2,000-square-foot areas of a store with unique points of view that intrigue shoppers without overwhelming them. That’s the trend now, to offer multiple concepts with a lot of theater and excitement, including maybe a wine bar, a coffee shop, a jewelry boutique, a pet boutique, all offering inspirational and aspirational things that are going to capture her attention and make her fall in love.”

The designer, responsible for more than 25 million square feet of retail space worldwide, continues, “The hardest thing of all now is to get people to come into your store. People ask me all the time whether brick-and-mortar stores are important anymore, and I tell them, ‘Yes, now more than ever,’ because even though people are shopping online, I believe they get sick of looking at a screen after a while. They want to touch something or go for a walk or look at a magazine, but I will tell you that there are very few stores in America today that look as good as a magazine page and therein lies the problem. If you spend the time to create environments in your stores that look as inspiring as some of the magazine pages that your customers are looking at, they will want to come in and look for ideas and they will want a piece of what they see.”

Up, Up and Away

Although Kyle Johansen, Executive Director of Merchandising at 16-store HOM Furniture Inc., describes the internet as “extremely important — almost your new front door today because most people who are going to buy furniture jump on a website first to get an idea of what’s out there,” — he says there is no question that the majority of home furnishings sold online today are lower-priced goods and that shoppers “will spend far more money if they walk into our stores.”

He relates: “We definitely want people to come in the stores, both for the experience and because we put a lot of effort into training our people so that they are knowledgeable about the furniture lines and what’s right for the consumer. Maybe a cheap sofa is right for you, but probably not, and when you buy online, they all look the same, and they have the same comfort level, which you can only guess at with your eyeballs. You might think, ‘That one looks comfy.’ Really? You don’t know that. What if when you sit in it, it’s too deep for you because you’re short? You don’t think about things like that until you sit on a sofa, or until you lay on a mattress that’s too firm or too soft. You don’t realize that if you’ve got a shoulder problem you should probably have a higher-end mattress that offers more support. The fact is, Casper will tell you that their mattress is perfect for everybody, but that’s baloney.”

Complicating matters is the fact that it can be difficult enough to judge quality in person, much less from a picture of a product on screen. “If you’re paying $399 for a sofa, the quality is probably pretty good for the price you are paying,” Johansen admits. “But I always tell people you get what you pay for. Don’t buy a $399 sofa and think it’s going to last for 20 years.”

The HOM merchandising executive has formed his opinions about how to communicate quality at vastly different price points thanks to HOM’s two flagship store presentations in the Minneapolis metro area, which include the mid- to upper-market HOM, the more promotionally priced Dock 86 format, and the high-end Gabberts brand all under one roof. Each attracts its own core customers. Known for outstanding presentation, every store in the chain employs full-time merchandisers “whose only job is to make it look good. They are not in charge of cleaning, or dusting or fluffing pillows,” says Johansen. “Because if you think that your salesperson is going to make your store look good, you are fooling yourself.

“Customers shopping Gabberts are looking for something unique, that’s of high quality, but something that’s specifically for them, and you can’t get custom furniture at $399 price points or even $499 or $599,” he says. “If you drive a Mercedes Benz, have a nice lake home and want something customized that will last, that fits your lifestyle, you’re not going to shop Dock 86, where it’s rows of furniture and looks like a clearance store and that’s what it’s meant to look like. We wouldn’t even walk that customer over there to show them. Then we have customers who walk through Gabberts and laugh. They point at pictures and they say, ‘OMG, somebody would actually pay $14,000 for a dining table?” Well, yes, they would, because it has an 18-step, hand-applied finish etc. ... It all depends on the consumer, because we have people who come in who want to rent because they can’t afford to buy, and then we have customers who come in who own jets. It’s two totally different people and they are not interested in the same thing, and we can’t talk to them in the same way.”

But Johansen and HOM can excite both and therein lies the key to the retailer’s success. “Cheap furniture is not hard to sell, because it’s all based on price,” he sums. “You can do that, and you can be great at it, but good luck, because nobody makes money in a race to the bottom.”