At a time when the ability to work with an interior designer is within the reach of more consumers than ever, thanks in large part to inexpensive online design services, little appears to be changing at the better end of the marketplace.

“The people who hire me are not do-it-yourselfers,” says Texas-based interior designer Kristi Hopper. “They are busy, have little design sense and know that they can’t pull it off themselves. They want something better than they can get at retail. They want an experience. They expect me to come up with innovative ideas that they could not think of themselves, and then to bring people to the table that can do the job; people they know they can trust because of my relationships with them.”

Though the designer has seen many changes in the two decades since she founded Kristi Hopper Designs, which specializes in both whole-home remodels and interior design, she says most people today are more aware of the interior design profession because of HGTV. “There was no Joanna Gaines when I first started my business, and I think that TV made people more open and receptive to using a designer, and the value of designers. That said, it’s also contributed to some unrealistic expectations in terms of budgets because the show producers get things at cost or have them donated. I have a client right now who said, ‘Well on TV, they said they could do a whole kitchen for $12,000.’ And I had to tell her, ‘Yes, but you want new cabinets, new everything, and you want to close off a door. That’s going to cost $50,000.’”

Getting Real

The key to happy clients now “is setting expectations up front and having a good contract,” Hopper relates. “I have a contract, and over the years I’ve learned to sit down with people and walk them through it. It says things like ‘There will be dust,’ because no matter how you prepare people for a mess, if you don’t talk about it, they’re always shocked and upset. So, I sit them down and look them in the eye and say, ‘We’ll do our best to keep the jobsite clean, but there will be dirt and you’ll need a housekeeper afterwards. I tell them I can send someone to them, but there will be an extra cost.

“It states that we won’t be there every day. It also says if you add something that is not on your contract, there’s going to be an extra charge, because people think, ‘Oh, she’s here, she can hang this light for me.’ When I explain it up front, they won’t be upset with me later.”

Additionally, the designer says, “The contract states my hourly rate and the rate of anybody who works for me. I spell out everything.” Hopper has updated her contract numerous times over the years to reflect things she’s learned the hard way. Now, for example, “it says if there’s a manufacturer defect, you can’t hold me liable. And if there is an act of God, you can’t hold me liable. It talks about contractors and their insurance. In other words, if anything goes wrong, the claim would be against the contractor and not me.

“Then, I have sheets called ‘What to Expect When you Get Countertops,’ and ‘What to Expect When You Get Wood Floors,’ and there is another for tile. There’s a lot wrapped up in each of those things and I go through all of it, because people don’t know. They don’t think about the fact that they have to clear off their countertops and take everything out from underneath the counters unless you tell them.”

Essentially, Hopper says, the most important thing for designers now is to be clear up front and to continually “update your contract throughout the course of your career. When something bad happens with any job, I believe it’s to teach you something, not to take you out. You learn from it and use it to make your contract and your projects better. Like adding the paragraphs about the manufacturer’s warranty and acts of God. I never had those in there before because I write my contracts myself to make them more approachable.”

As for not using an attorney, she says: “I had an attorney write my contract and it was 10 pages long and I was like, ‘Dude! I can’t even read this so I’m not going to make my clients read it. And they won’t, so it just makes me look like I’m ridiculous and nobody wants that. I have to be approachable. People hire me because they like me. There are a lot of designers in Dallas, and there’s enough business for everybody, but my first job is to sell myself, right? The second is psychology and figuring out how to relate to the client and the third is project management: how I’m going to work in their home.”

Throughout a project, ongoing communication remains key. “For instance, we ordered a custom sofa for a client and it’s being made for her. I tell people up front how many weeks it should take, and when to expect it. Even so, at the beginning of this week, I asked my assistant to find out where the furniture is in the manufacturing process so we could give the client an update.”

Managing expectations in this way stems largely from Hopper’s corporate background (she worked for Canon as National Sales Operations Manager for a decade, with more than 80 people reporting to her). “It was wonderful training that helps me manage a lot of projects at once these days,” she sums.

Show Them the Real You

For interior designer Barbara Lewis, with design studios based on Long Island, NY, and in Stamford, CT, serving affluent clients goes hand in hand with the visibility and validation that comes along with high-profile showhouse work.

“Unless it’s a direct referral, people interested in working with a designer start off by Googling names and looking at your website. So, you have to have a cohesive, easy-to-navigate website today that’s packed with really wonderful photography that shows off your work,” she says. “But showhouse projects take you beyond taking your personal work and putting it up on a website. It’s a seal of approval that someone else thinks enough of you to have you be a part of their show, to help them look good.”

Most recently, Lewis was a featured designer for the prestigious Rooms With a View at the Southport Congregational Church, where she created a classic, yet current, entry vignette inspired by Albert Hadley. (Hadley himself was a church member and until his death served as the show’s honorary chairman.) Founded 25 years ago, past designers associated with the annual fundraiser have included Bunny Williams, Thom Filicia, Charlotte Moss and Alexa Hampton, among others.

The same month, Lewis was also a featured designer at Holiday House New York, where she created a bar lounge inspired by the Café Society of 1960s Manhattan. This, on the heels of the critical acclaim she received earlier that year for her work at Holiday House Hamptons.

Though the designer acknowledges the impact of the internet, with its saturation of information and photographs that lead consumers to think they can just point and click their way to good design, she notes, “That person is really not my client.” But in an era of transparency, she too points to the importance of “having the right contract. Either they are going to agree to your terms and sign it, or they’re not your client,” she says.

“My clients still expect me to do the entire job for them, right down to the accessories, with a lot of customization. And as any designer will tell you, you do your best work when they give you free rein because they trust you. I’ve earned that trust through experience, transparency and a long career.”

Acing the Interview

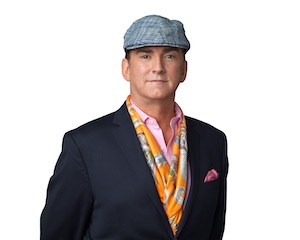

Vice President of Hospitality for architecture, engineering and design firm Baskervill, the 13th largest hospitality firm in the U.S., Gary Inman concentrates mainly on that sector these days. But the designer still has his hand in whole-house projects, typically when the houses are large and important enough to have a name, such as Millstone Manor, a recently completed country estate. “We’re hired because the client knows we have the capacity to handle the scale of their project,” Inman says.

Inman, who got his start as a fashion designer in New York, working with the likes of Vivienne Westwood, Mary McFadden and Liz Claiborne before moving into the world of interiors, has witnessed “a fundamental paradigm shift” in the nearly three decades since he began. “There was no AutoCAD when I started; everything was still manual. And most of the resources were truly for the trade only,” he says. “As designers, we had access to so many things that the public did not, and I appreciate that more these days than I might have at the time.

“What I think my high-end residential clients are looking for when they hire a true designer — and I think to some extent this is true in hospitality as well — is a person who has the capacity to give them the best products and design solutions available. Because they can see so much on the internet, and they can shop around, I tell them, ‘I will edit the world for you.’ Most people don’t have the ability to edit, process or create the cohesive connections between a myriad of design elements. It’s overwhelming for most. As a designer, I’m able to weave those things together.

“I think one of the things my clients value most about working with me is my capacity to look at everything, all the potential things they could have in their home, and then edit it down and choose the right things to tell their story in a way that feels very personal to them.”

Like Lewis, Inman says, “There is value in being at a point in your career where you’ve earned a certain credibility. Obviously, you always have to be cultivating work, but it isn’t like the first years when you kind of take what comes along. In the early days, I thought of it as an audition, and I felt I had to really get them to like me and be impressed by my portfolio. It was all about trying to prove to a potential client that I could be valuable to them, that I had the right taste and the right skillset. It was really a very one-side equation.

“After I practiced for about 10 years and had all these issues come up that teach you lessons,” he shares, “I developed a certain degree of wisdom about the process of how to deliver design to clients and how to be a good practitioner. I learned to spot the tell-tale signs when people had decision-making issues, for instance, and to steer clear when a person has anxiety about making small decisions because when you’re creating a large home, there are going to be thousands of decisions and you’ll never achieve any momentum. Now, when I go into an interview, I look at it very differently. I’ve learned to interview them as much as they are interviewing me and to trust my instincts.”

To deliver a complete experience, Inman says, the most important thing “is to be passionate, to really make the story about them and not about yourself. I don’t have a signature style because I’m always interpreting someone else’s dream. It’s about having empathy and caring about their lives and creating a place that reflects who they are. And, it’s a powerful feeling when you’ve moved someone emotionally, when they are almost speechless about their home. I love that. It’s the reason I’m still doing it almost 30 years later.”